2025 Venice Biennale Architecture

Adrift

“I have been shaped by the tides of my journey—adrift, I searched; anchored, I transformed, finding beauty in the connections that ground me.”

Adrift from my homeland, I have anchored and transformed, much like an oyster on Ningy-Ningy Country. My LIVING BELONGING reflects my journey of transformation and resilience through connection.

Just as oyster larvae drift with the tides in search of a foundation, I have found my own—reshaping and evolving with each new chapter. The landscapes that have shaped me—the Philippines, Dubai, and Redcliffe are woven with the rhythms of COUNTRY.

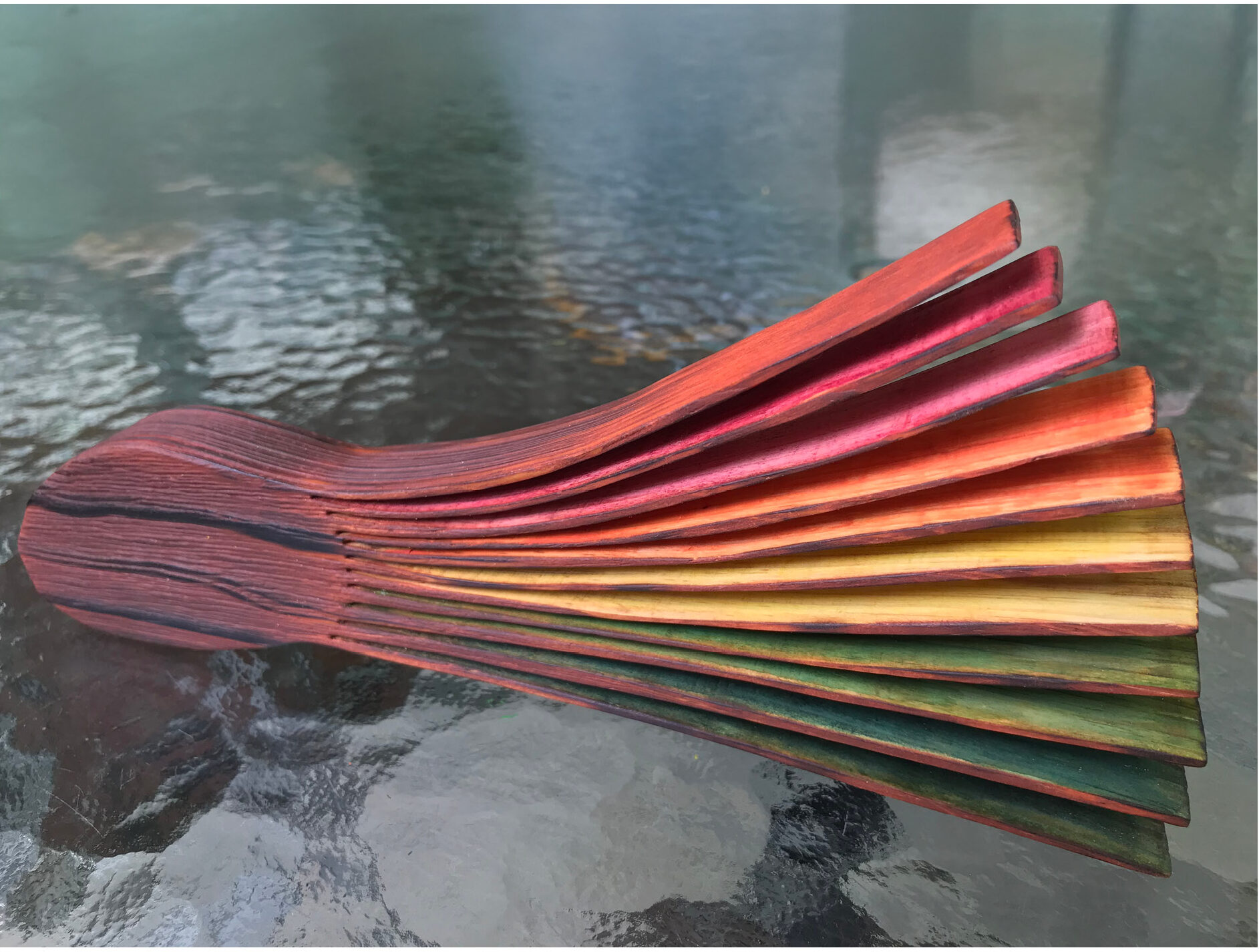

The material I worked with is scrap timber, once discarded, but now it carries the imprint of time, and environment. Each layer and colour of the wood, every bend and burn of my process of making represents my transformation. My work is a dialogue between material, place, and self—an ongoing exploration of belonging.

As an oyster reef creates shelter, my LIVING BELONGING invites a space for reflection—asking: Have you drifted, and what anchors you? How does COUNTRY connect you to HOME—and your own BELONGING?

Australia → Venice Biennale, Australian Pavilion | 2025

Adrift, my Living Belonging, emerged from a unique Australian design studio, presented as part of the Australian Pavilion exhibition HOME: Country as Creative Process at the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale.

Delivered across Australia and culminating in an international exhibition, the studio invited us to create a Living Belonging piece—immersing ourselves in Country, identity, and belonging. Design was approached not as a fixed outcome, but as an evolving process of reflection, listening, and response.

The project reflects both personal and collective journeys, situating individual experience within a shared voice across Country and distance. Seeing the work in Venice was a grounding and humbling moment, marking an important milestone in my architectural practice. Documentation of my journey is available via the UQADP website.

“Home is something I carry within myself, evolving as I do”

What is home?

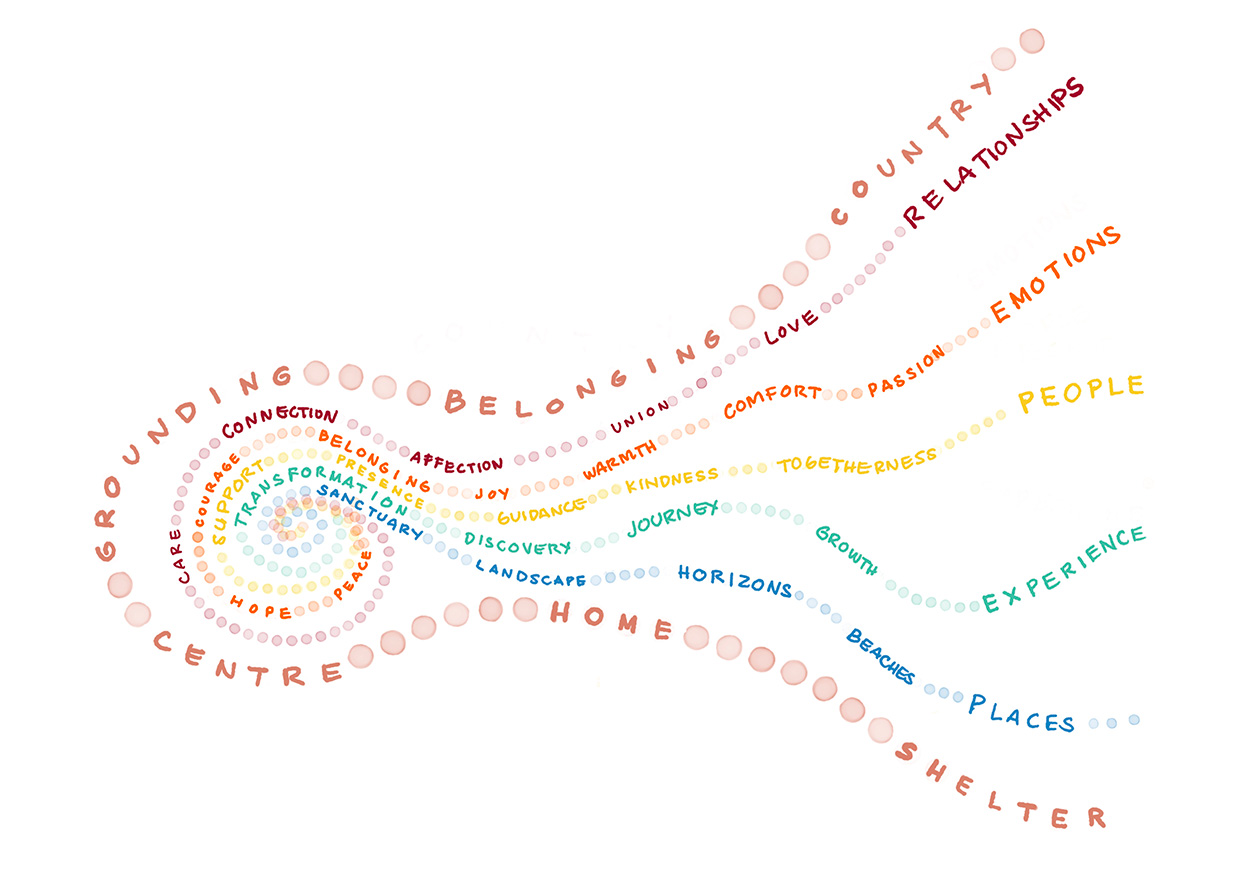

The project began with a simple yet profound question: What is home?

In shared yarning circles, we unfolded memory—bringing stories, found belongings, and fragments of lived experience into collective exchange. Across distance, laughter and tears intertwined, revealing home as something felt, remembered and shared.

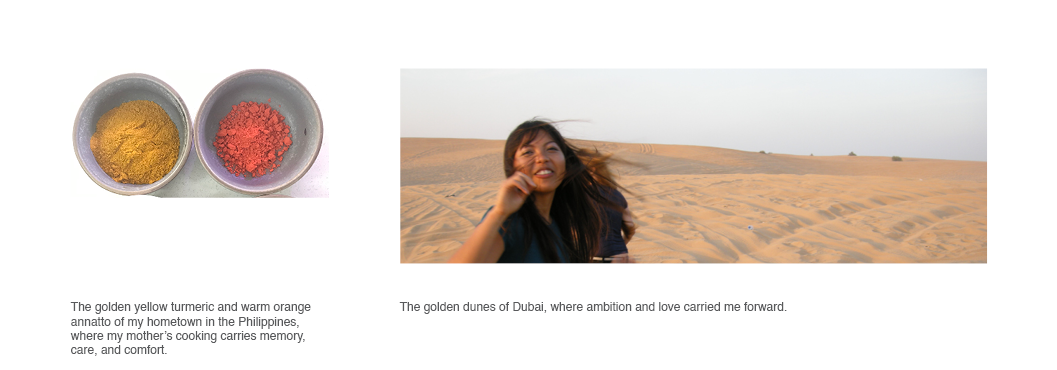

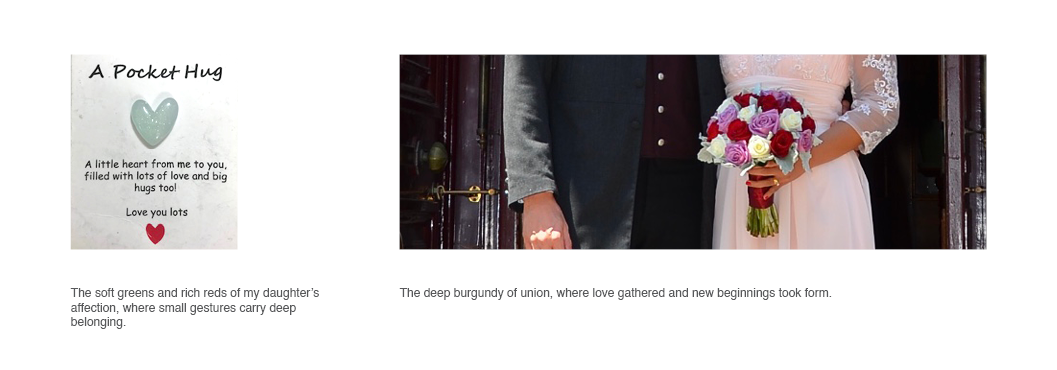

For me, home is never fixed. It drifts and anchors, transforming in quiet ways. Memories of people, places, and moments of care and joy gather within me, gentle anchors slowly shaping who I am becoming. Within these memories, colours awaken moments of joy, connection, and belonging—pieces of home that travel with me, carried softly wherever I go.

What is Country?

Through listening to Aboriginal voices, I learned that Country is not land alone, but a living system of stories, relationships, care, and responsibility. My understanding was shaped on the Redcliffe Peninsula, on Ningy-Ningy Country, where my family and I found grounding and connection.

Expression

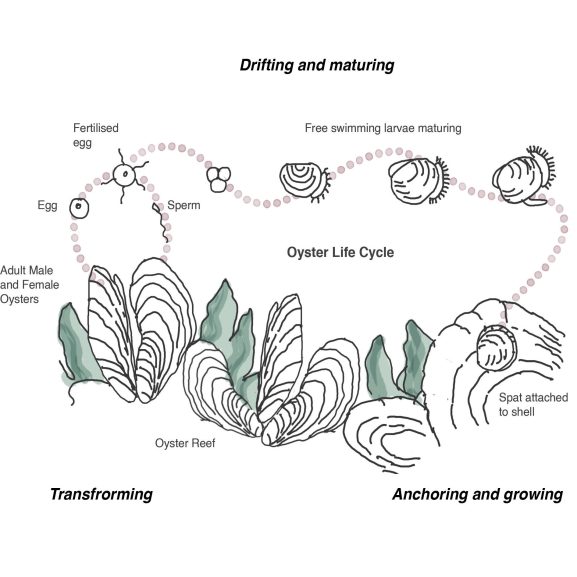

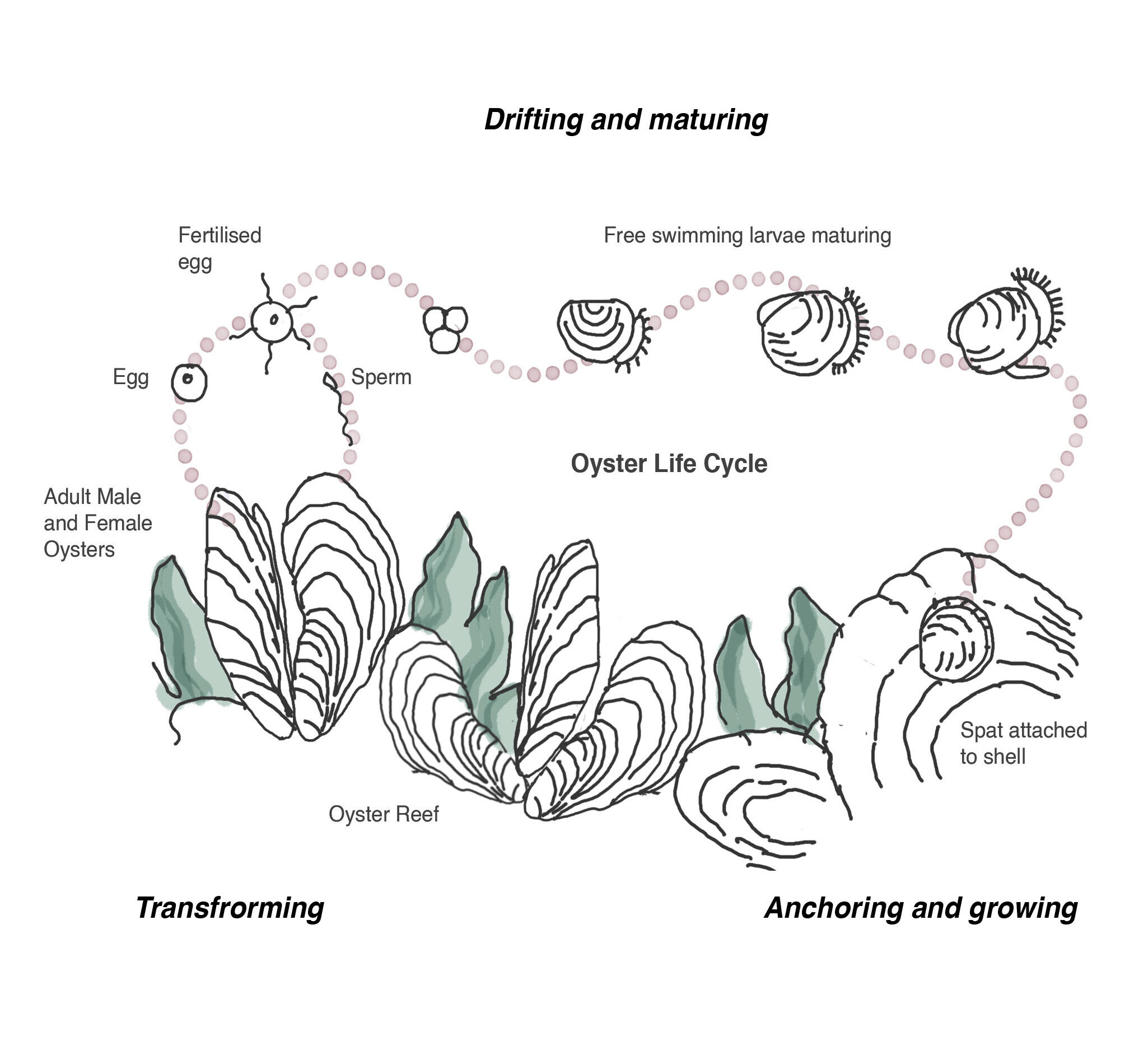

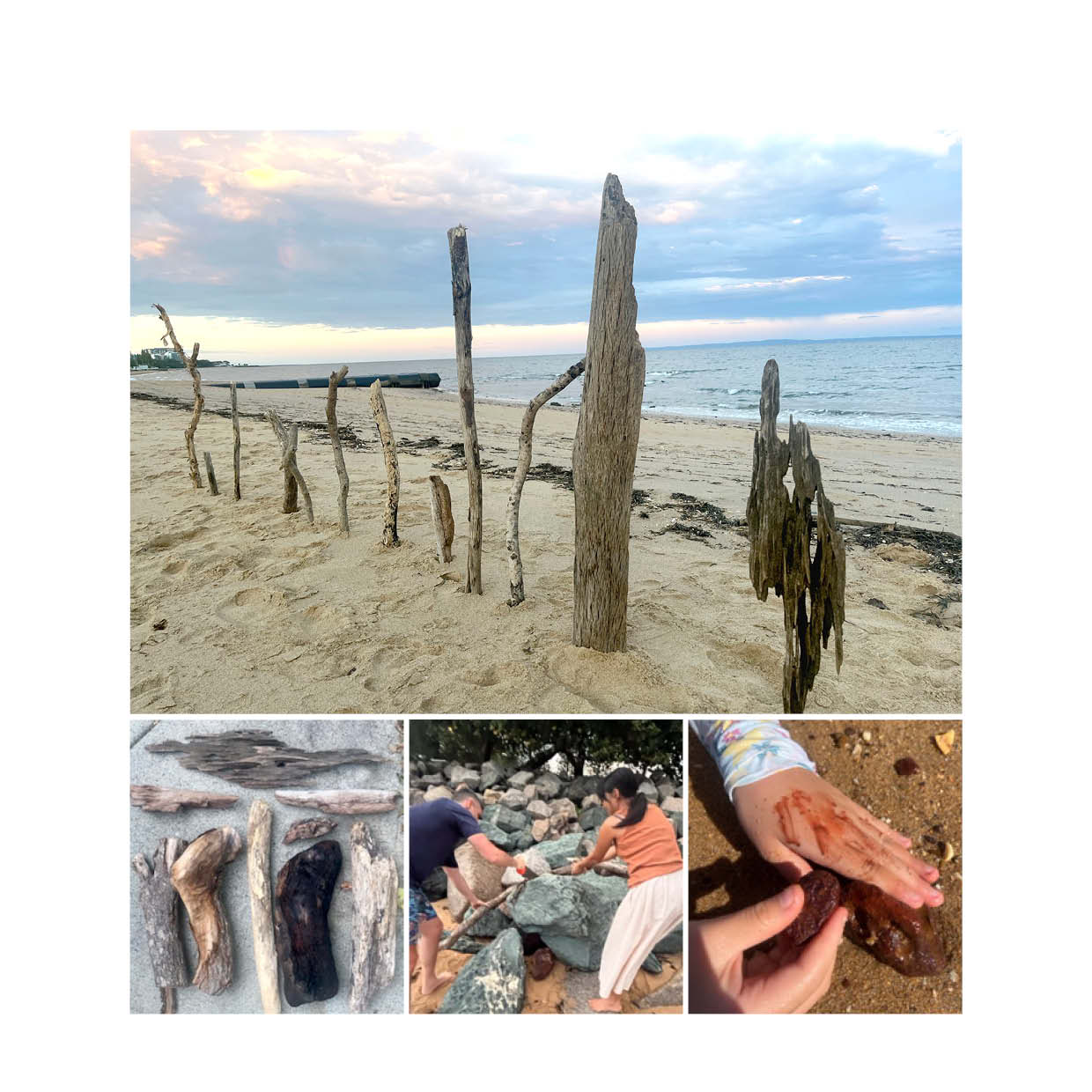

The Ningy-Ningy people, Traditional Owners of the Redcliffe Peninsula—whose name means oyster—hold a profound connection to the waters of their Country, where oysters have long sustained community and culture. From this relationship, the oyster emerged as a powerful metaphor expressing my own journey toward belonging.

Drifting with the tides, anchoring to place, and gradually forming a reef, the oyster reflects my experiences of migration, settlement, and transformation. Its resilience, and its capacity to create shelter through collective growth, articulate my evolving understanding of home and belonging.

Conceptual Framework

This work frames belonging through oyster ecology, tracing identity as a movement of drifting, anchoring, and transforming through gradual accretion. Like oyster larvae carried by shifting tides, my migration experience unfolds between fluidity and stability. The essence of this journey is captured in fluid strands—representing the lived experiences of relationships, emotions, Country, and places—which drift inward and converge at a spiral centre. Here, these fragments anchor and calcify into collective shelter. Through this metaphor, home emerges not as a fixed destination, but as a living, relational structure shaped through time, care, and the shared weight of connection.

Materiality

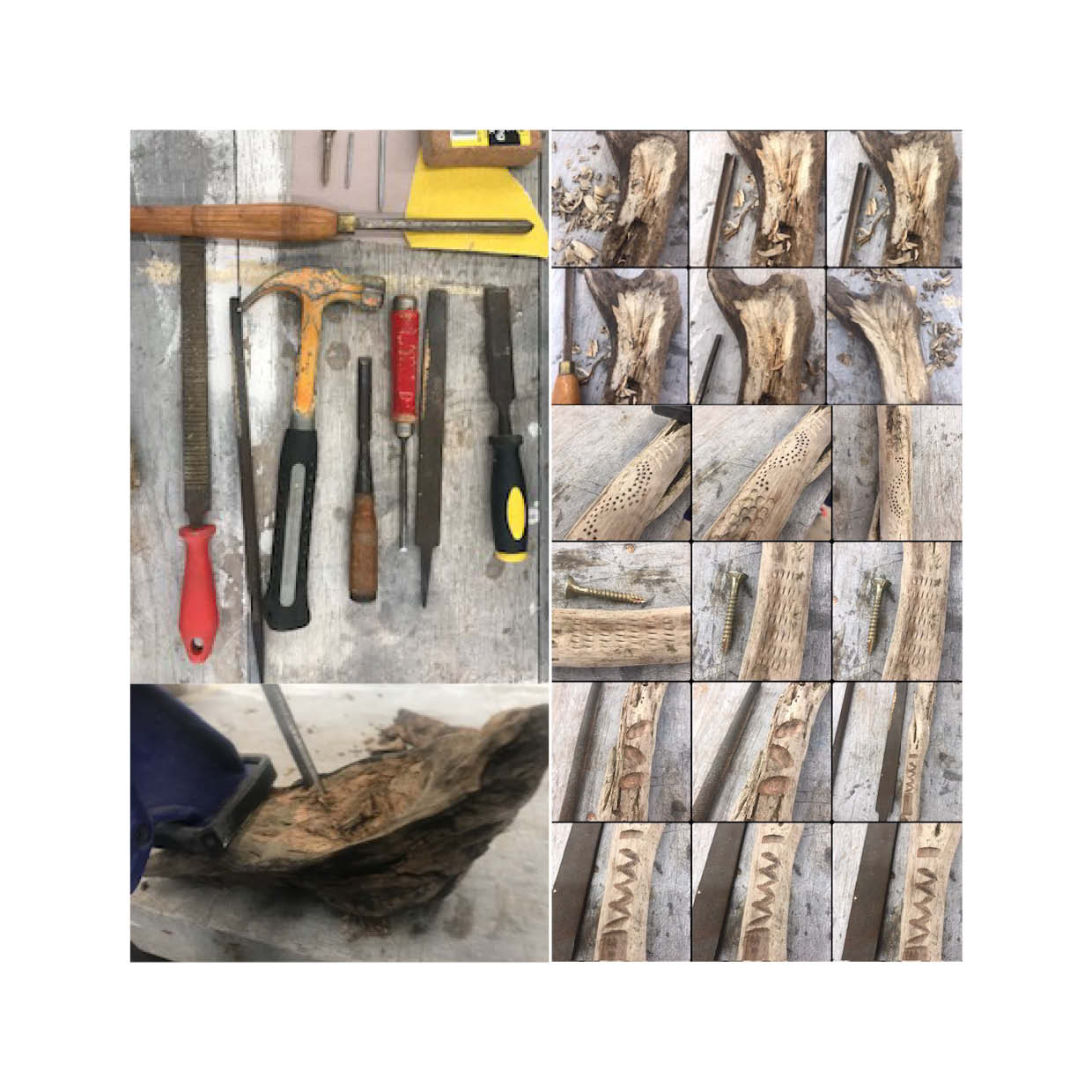

The materiality of wood and pigment embodies this ecological journey. Treated as responsive, memory-bearing mediums, the timber undergoes soaking, cutting, burning, splaying, and reshaping—simulating environmental pressures shaped by both nature and human intervention, echoing the conditions of migration. Pigments translate memory into colour—an anchor through displacement and uncertainty. Through friction and adaptation, transformation unfolds. The resulting textures and scars are not damage; they are “material witnesses” to resilience, recording how lived experience leaves its mark on the self

Architecture

The making is guided by artists who listen closely to material and place—Judy Watson, Henrique Oliveira, and Christian Burchard. Their works reveal material as a vessel of memory, reclaimed matter as a source of renewed beauty, and natural forces as collaborators that allow form to emerge over time.

Judy Watson, a Waanyi artist born in Australia in 1959, draws on her Aboriginal heritage through matrilineal connections. In The Guardians Spirits, the female form becomes a vessel for ancestry, memory, and care. Her use of natural powder pigment on plywood as an expression of land and lived experience informs my own approach to colour—where memory, place, and belonging are translated into material form rather than surface gesture.

Henrique Oliveira, a Brazilian artist, inspired me to embrace reclaimed timber, revealing beauty in what is discarded. His work, such as Corupia, transforms used plywood from construction hoardings into monumental, organic forms that evoke growth, movement, and the dialogue between nature and the built environment.

Christian Burchard, a German-born, US-based sculptor, explores the natural responsiveness and transformation of wood. His work with wet Pacific Madrone burl—cut thin and left to dry naturally—reveals how timber reacts to its environment, twisting, warping, and shifting over time. His process influenced my exploration of working with wet wood, allowing material response to become an active driver in the design and making process.

The Making and Process

The work began on Country, collecting driftwood with my family along the shoreline. Each piece—shaped by water, time, and movement—carried its own story, the longest-drifting showing the most character. Meanwhile, my daughter discovered red ochre on the beach, which released a vibrant pigment when rubbed with seawater, becoming part of the work.

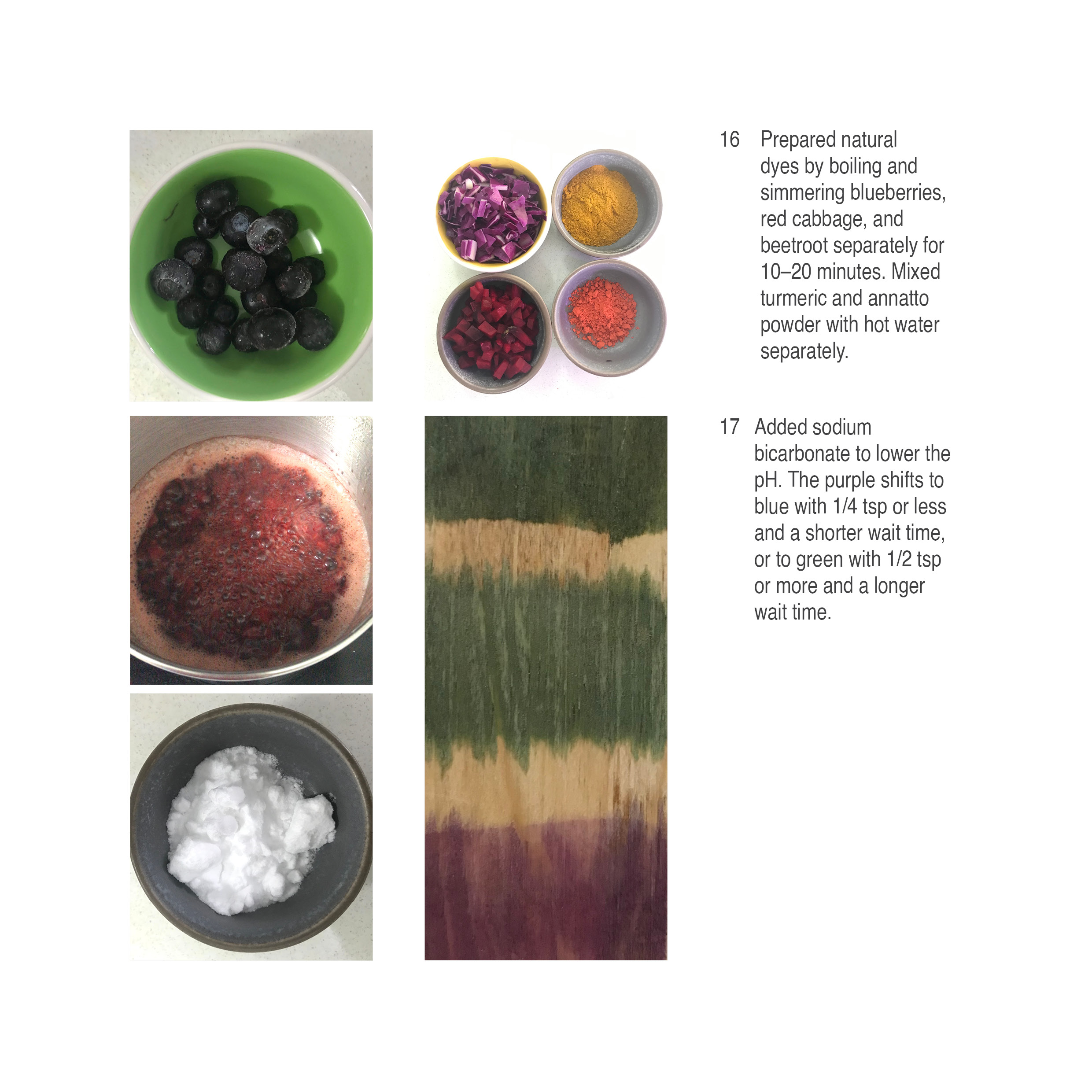

At home, kitchen pigments were explored—turmeric, annatto, cabbage, onion, beetroot, and blueberries. Through research and experimentation, I discovered that sodium bicarbonate could shift pH-sensitive pigments, transforming purples and reds into blues and greens.

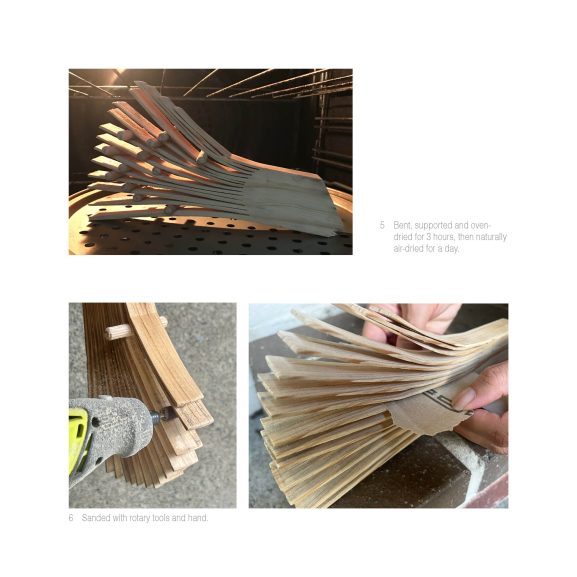

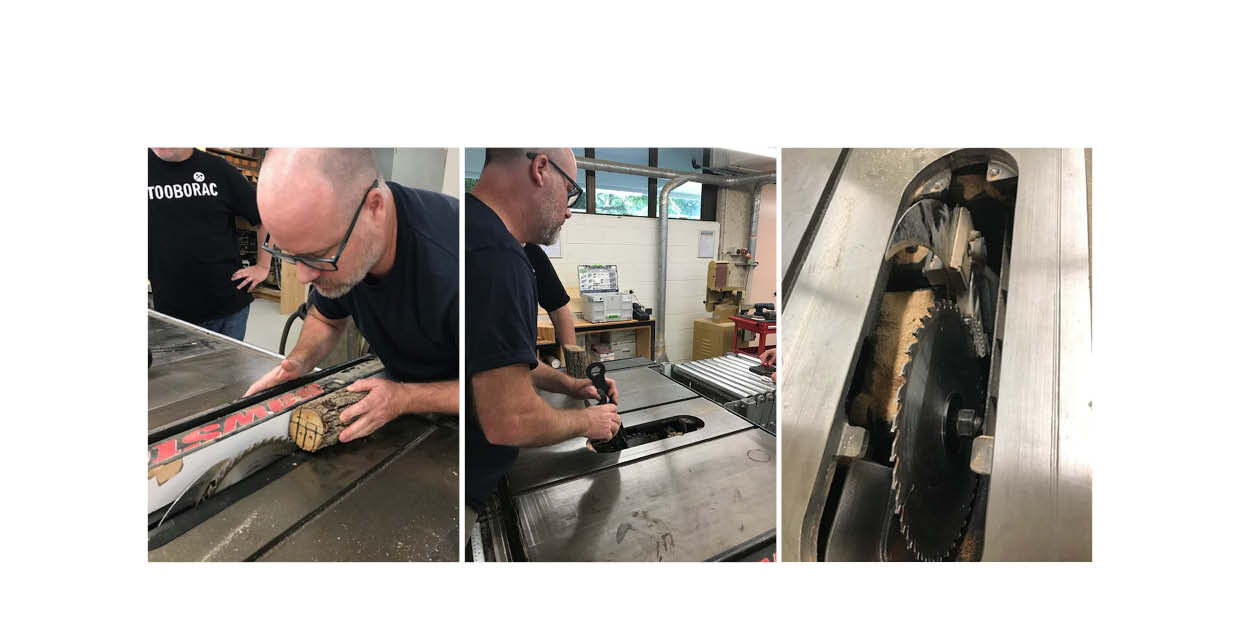

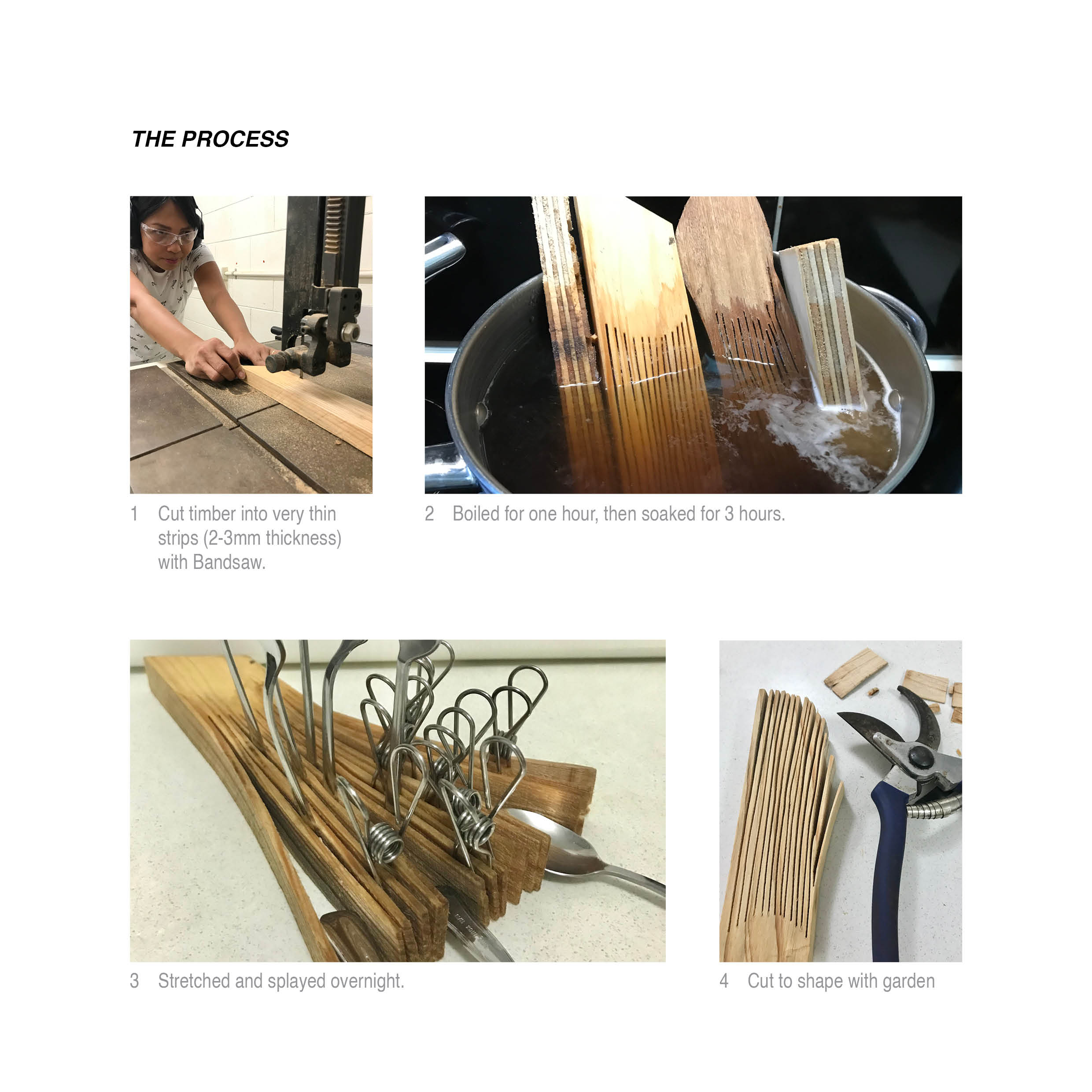

Textures, patterns, and reactions of wood were first explored by hand, then with mechanical tools. However, cutting wet wood proved unsafe in the University workshop making the method unviable.

Rather than abandoning the idea of working with wet wood, the process adapted, shifting the methods. From driftwood, I turned to scrap timbers—wood already displaced, stored, and waiting in the workshop. Among the timbers, the soft pine proved the most responsive, willing to bend, break, and adapt. The spotted gum, resisted cutting and shaping, while the plywood crumbled under pressure.

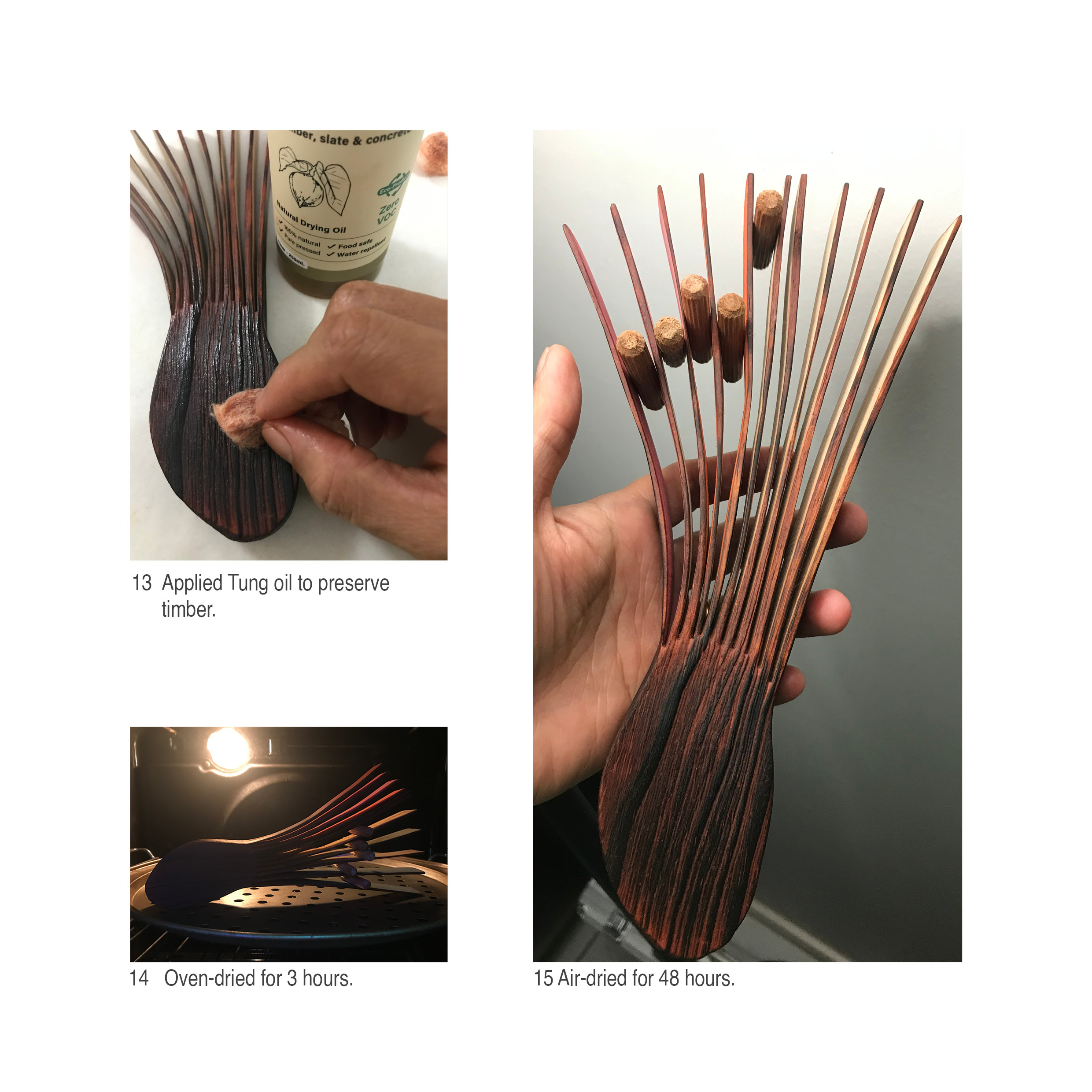

I reversed Christian Burchard’s method: the timber was cut dry, then soaked, boiled, and splayed under pressure. Time constraints accelerated drying in the oven, forcing transformation rather than allowing it to unfold naturally.

The timber resisted the organic curls I had hoped for, stiffening and holding tension. Four of the fifteen strips broke under pressure, requiring reshaping. Every action met with resistance, each adjustment shaping the next.

Apprehensive, yet I continued. I torched the final piece, and as I brushed away the char, older patterns surfaced—beauty emerging through the material’s response to pressure.

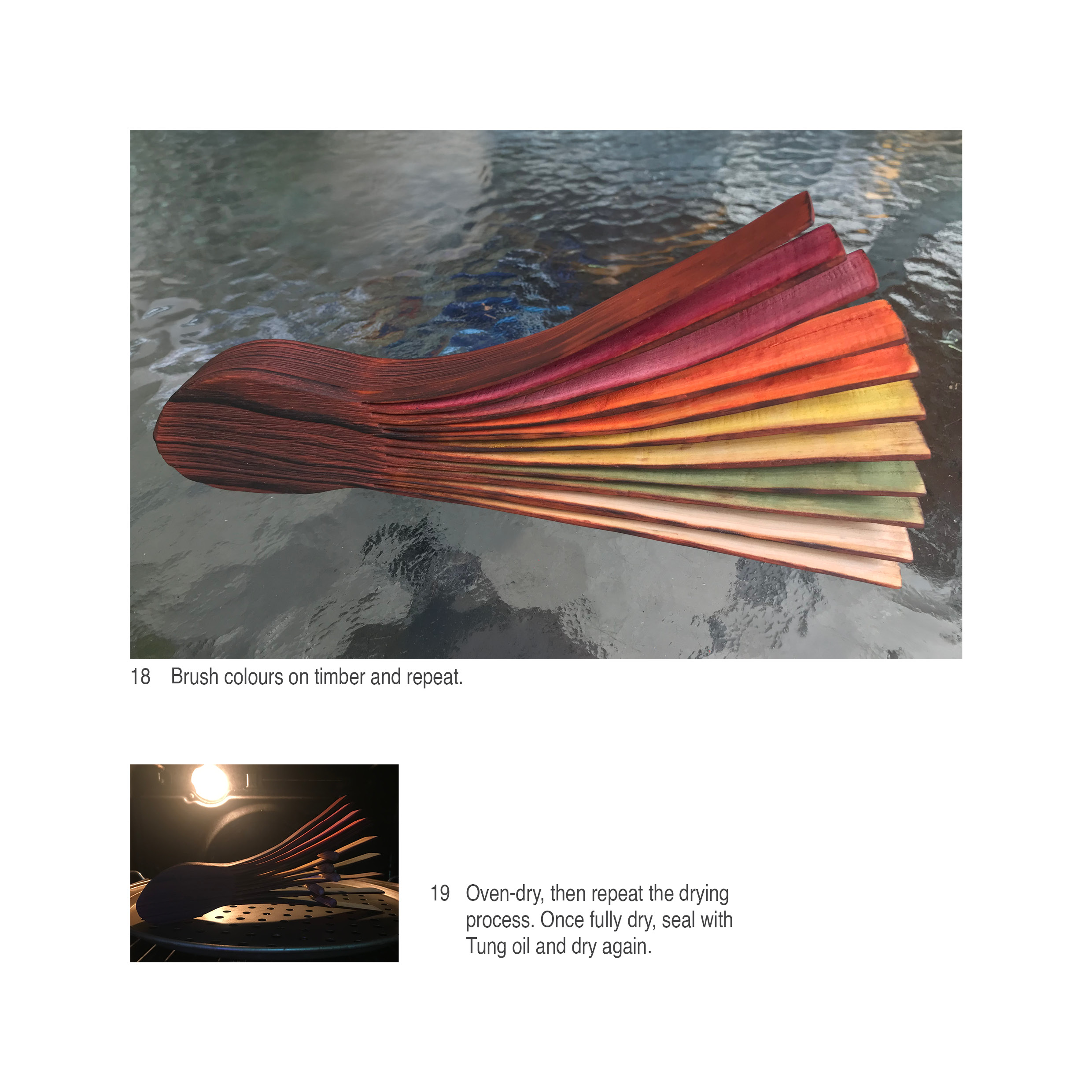

Applying red ochre enriched the timber’s grain and natural beauty. As some pigment rubbed away during handling, I sealed the surface with tung oil, protecting and preserving both the wood and its colour.

Working with pigments became the most delicate stage of the process, especially with the pH-sensitive blueberries and cabbage. Transforming their purples into greens and blues with sodium bicarbonate demanded precision. Small variations in timing or quantity altered the colour entirely. Until sealed with tung oil, the pigments remained unsettled; greens slowly dissolved while blues continue to shift hues on the timber through oxidation.

Through material process, the material guided each step, its resistance and reactions shaping the piece and revealing form through every interaction.

Reflection

Working with the materials revealed that transformation arises through responsiveness, not force—every moment demanded listening as much as acting. When methods were reversed and accelerated, the wood asserted itself: it resisted, fractured, and held tension. Burning the final piece required both courage and trust, allowing uncertainty to shape the form and reveal an unexpected, charred beauty. The shifting pigments further highlighted the delicate, time-bound nature of change, where the degree of care determines whether colour settles or fades.

Sealing the timber with tung oil began as a practical step to preserve pigments. I later discovered its Chinese origins, historically used to waterproof the hulls of boats and vessels. This necessity became a profound gesture of care, connecting the work to my heritage and reflecting on Country as a keeper of stories across generations.

I realised the oyster’s life cycle mirrored my own process. I drifted, exploring without fixed outcomes; anchored when I chose scrap timber and adapted methods; and I transformed alongside the material. As time, environment, and handling left their marks, letting memory, meaning, and form settle.

Through this, I learned to let go and to listen deeply—to material, process, and circumstance—embracing uncertainty, change, and commitment. Belonging emerged as something living, shaped through relationships, memory, and place. My family remained my anchor throughout, a constant reminder that the ‘reef’ of belonging is never built in solitude, but through profound connection.

As the artwork evolved, I recognised fragments of my journey within its fibres, textures, and scars; it had become my living sense of belonging. Sending it to Venice carried a quiet weight, knowing its destiny is to be eventually released and destroyed. This insight now carries into my design thinking: architecture, like making, is a relational process. Transformation emerges through listening and dialogue, allowing spaces to evolve alongside the lives and memories they hold.

“Yet impermanence revealed that belonging resides not in permanence, but in experiences, connections, and transformations left behind.”